Interview: Shingo Kanagawa

Individual Narratives

An interview with Shingo Kanagawa by Kristian Häggblom

In this interview, Shingo Kanagawa speaks about the process behind his well received book Father, the motivation behind it and continuation of the project. He also kindly shares with us some images from an upcoming project about his aunty, and touches on his plans to explore the idea of faith.

Kristian Häggblom: How is your father?

Shingo Kanagawa: He is very fine, thank you.

KH: Can you remember the point when you decided to start photographing your father? How did you make this important decision?

SK: In September 2008 my father disappeared. He came home two weeks later but after that he stopped working in spite of having debts. I was having a difficult time making photographs and I was a little lost and couldn’t find subject matter. When I heard about my father's difficult situation, I decided to start photographing him to both help him and progress with my work.

KH: Did you make the decision believing photography could be a powerful tool for change? Or was it more personal?

SK: I didn't make a definitive decision for change, but taking photographs of my father brought many changes as a result. Therefore, I think photography is a very good tool to represent not only personal subjects, but also a sense towards “personal” feeling and perspective. What it means to be “personal” is complex and it varies by cultures, individuals and many other factors. Photography can help to realise this.

It is not easy for me to understand how I should be commended for being so brave and open. It may be brave for someone to make art about their family, but it's not for me. This is how I somewhat define ‘personal’ in regards to my project.

KH: It is a very personal project and you should be commended for being so brave and open. How did your family react? And especially to the publication as it makes the work so public?

SK: My father celebrated the publication and he was pleased with my success. Maybe, deep down, he thinks that subject of depression and disappearance it is not his issue, somewhere in his heart, and it also applies to me.

KH: The breakdown of contemporary society is a worldwide crisis (in my opinion) but it is only recently that it has become more discussed in Japanese society. There are also some issues particularly associated with Japan, for example ‘hikikomori'*. Why do you think Japan is opening up more about social issues?

SK: I'm sorry, I'm not good at thinking about “Japan is...”. I try to focus in more familiar things around me.

KH: The personal diary is written in a very matter-of-fact way. But it is also very personal and insightful, I couldn’t stop reading once I had started. What was your aim with the text? And how did it get included in the book?

SK: It is important for me that the diary is not subordinate to the photographs, and vice versa. They influence each other, but they are autonomous. Texts and photographs have different structures and I needed both of them to tell the story of my father.

KH: Many photographers who work with documentary are using other methods with their images to expand the outcomes, such as text, archival images, collected objects, etc. Like a detective making a dossier. Are there any photographers or projects that influenced you?

SK: Many people and works and projects influenced me. Recently, I am interested in the works of W.G. Sebald

KH: It is very interesting that you also then gave your father a camera and asked him to take a picture a day. Can you tell me about how you decided on this? What did you hope for?

SK: I didn't have a clear intention nor aim when I asked him to photograph himself. Though the project started with my suggestion, it is also true that the relationship between me and my father directed the outcomes.

KH: And he is still making a portrait everyday?

SK: He still is! Although it is still difficult and I am reluctant to give a name or meaning to this project.

KH: You have been working on a new project about your aunty and had an exhibition recently. Can you please tell us about this project and exhibition?

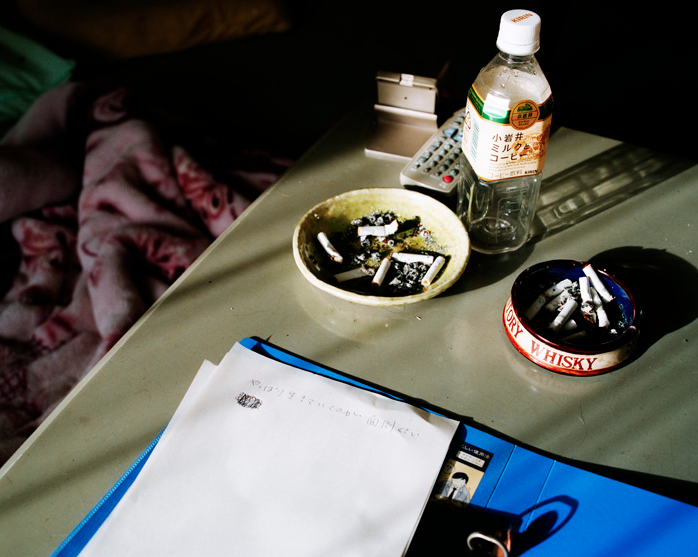

SK: My aunt, who is my father's elder sister, disappeared more than 20 years ago.

I have only met her and I have only small memories of her. I know she lived in a hospital in 2010 and it was then that I started taking photographs of her. She has dementia and can’t remember the past. She calls me Makoto, but I don't know who Makoto is?

KH: What else inspires you other than photography?

SK: Many things, especially real life individual narratives.

KH: What next for Kanagawa-san?

SK: Now I'm writing about faith. At first, I started to go to churches to survey and then make artwork. This lead to me being baptized. Believing in God is so difficult to understand but I am interested.

Photographs and memory are, of course, inherently bound together. Photographs link to the moment, or place, or person that they depict, even after their demise. They are markers and memorials, often trusted beyond their capacity, altering our recollection of what really went on, fabricating what feel like memories. I get the feeling, as I revisit this book over and over, that the act of laying down these memories acknowledges that these images construct an imperfect and incomplete portrait. They are what Kimura can peg together through a set of imperfect tools: a dog, a photo album and conversations.