Interview: Kazuma Obara Part 1

Silent Histories - Part 1

An Interview with Kazuma Obara by Kristian Haggblom

Kazuma Obara's Silent Histories is a delicate and complex look at the devastation of war. In this interview with Dr. Kristian Haggblom, Obara discusses the origins and process behind the creation of his first photobook, and the intricacies of telling the story of a hidden generation of Japanese people.

This interview was first conducted in 2014 and continued in 2018 after a meeting in

Tokyo to discuss the Tsuka Project.

"I never told my mother that I was teased at school. I felt sorry for my mother, that she might feel guilty that she wasn’t injured. One day my mother said, ‘They can operate on you for your leg and put on a new one in the future. When the time comes, I will give you mine."

Excerpt from Silent Histories

Kristian Haggblom: I understand that you worked in the Japanese finance industry while also being a keen photographer?

Kazuma Obara: When I was 16-years-old 9/11 happened in America. After this catastrophic event, I strongly focused on international issues, with a keen interest in photojournalism. I started taking photographs when I was 18-years- old while I was a university student. I traveled to many developing countries and attempted to capture some social problems. I also did a three-month project in the slums of Nairobi and made a short documentary video.

Following this I then began work in the financial industry, but wanted to continue with my photography so I also attended a six-month photojournalism course that took place over weekends. After I graduated I was very inspired and decided to quit my job to work in freelance photojournalism. I planned to quit at the end of March 2011 but the East-Japan 3/11 tsunami and nuclear accident happened so I quit a bit earlier and started documenting.

The Nairobi documentaries can been seen on Youtube in two parts (Japanese only)

KH: Although this interview is about your photobook Silent Histories, can you elaborate briefly on your experiences in the Fukushima region post 3/11?

KO: My homeland is the Tohoku region where most of the devastation occurred. I have lots of friends whose houses were located along the coast. One of my best friend’s houses was completely destroyed by the tsunami and his grandfather died due to the destruction. That place was very familiar to me, so photographing the disaster was not only work – it was personal.

One of my projects from this time that is featured in my book Reset: Beyond Fukushima. It focuses on employees who were/are working at Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant. Although 80% of all workers were from Fukushima and became refugees or victims, they were hidden by the government and TEPCO. My photographs attempted to reveal their real situation and their existence – to give a face to the hidden and unknown victims.

KH: Can you tell us what it is like psychologically to be inside the nuclear plant? And is it difficult to photograph under such circumstances?

KO: During the first two hours after entering the site, I was really nervous, I was really afraid of an explosion at the plant. At that time, the radiation levels were about 100 times the dose of normal circumstances. However workers needed to take off their mask and eat lunch.

I had to enter the site with the workers, so under the circumstances, especially inside some of the buildings, it was impossible to bring a DSLR. So I used a toy camera which is very small and discrete. A number of workers used mobile phones, so I did the same, it was easier to capture moments with small digital devices. That was unofficial shooting, so I had to be really careful when selecting which photos were published.

"It is my hope that portraits of such people open up an opportunity for the public to meet these invisible beings which in turn helps the public to think about the devastating situations that have taken place."

KH: Devastating and tragic events are hard to photograph, and there has been much work done post 3/11 that engages directly with the affected areas. What is your approach, if you have such a methodology and what do you think photographs can bring to the conversation of very serious social issues?

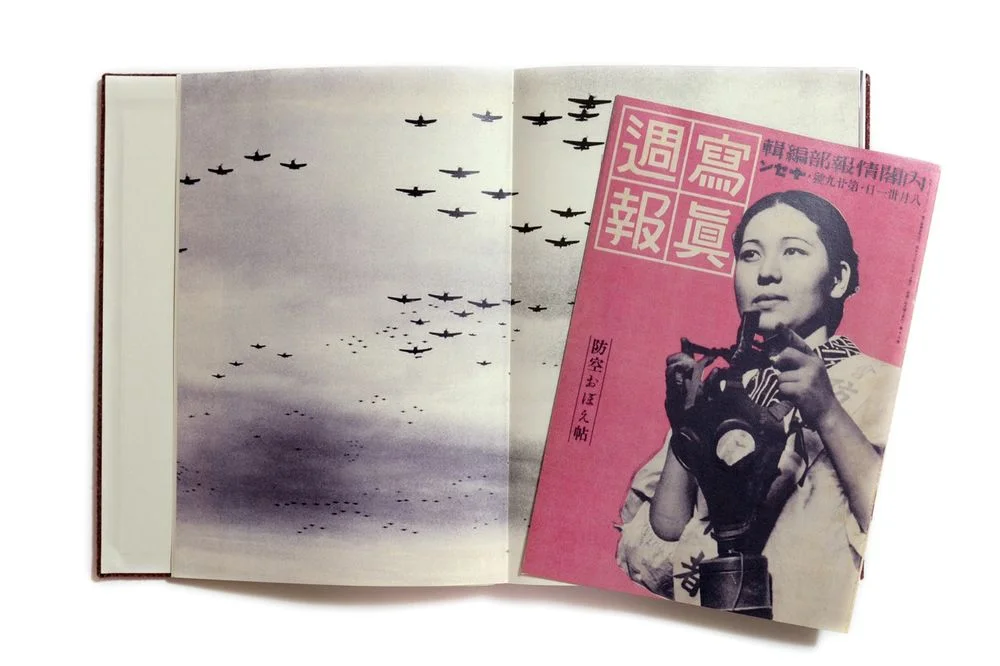

KO: My approach is very simple and begins with talking to people. It is a fairly straightforward documentary approach. I like to be on the ground and meet people face to face (the researcher and the subject). For my projects about 3/11 and WWII, I largely work with people who have become invisible due to circumstances beyond their control. It is my hope that portraits of such people open up an opportunity for the public to meet these invisible beings which in turn helps the public to think about the devastating situations that have taken place. Though I also think that the portraits are not enough to fully explain the circumstances I am documenting. Therefore other I introduce other elements into my projects to create further narratives and background information. These include extended interviews, historical/found photographs, propaganda magazines and so on. These play a crucial role in outlining the situations from several perspectives. The photograph is quintessential here and I believe that photographs can play a vey important role to remind of what is important and what we should protect.

KH: Many contemporary photographers are using this technique, especially in photobooks, of combining text, archival images, bespoke design, text, etc. A mode often used in what is now considered ‘New Documentary’. What other recent or older photobooks influenced the production of Silent Histories?

KO: This book was made when I was a participate of the handmade photobook workshop with photographer/story teller Jan Rosseel and photo editor/curator Yumi Goto in Tokyo at Reminders Photography Stronghold (RPS). This workshop gave me a lot of ideas. So their ideas, especially Jan’s book Belgian Autumn fascinated me. I am also influenced by Colors Magazine and its design, layout and content. Every time I was confused, I went back to two books: London/Wales by Robert Frank and Certificate No. 000358/ by Robert Knoth and Antoinette de Jong.

Silent Histories was the first time for me to make a hand made photobook. So after starting the handmade photobook I found I was worrying too much about technical problems: how to use these found photos and other historical material as well as the mechanism and structure of the narrative. Sometimes I forgot my main goal, but the aforementioned books and guidance from RPS made me focus on the main aim of my book.

KH: Where and how did you source the archival images for Silent Histories, and was the selection process difficult? Did you choose the archival photographs and shoot for them or did it work more fluidly?

KO: From the beginning of this project I decided to collect historical material. This was largely influenced by the fact that with the project of workers from Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Plant, I felt that photographs alone could not document the full extent of the situation. I felt it needed something else beyond interviews to gauge the intensity these men went through.

In regards to Silent Histories, my generation and for those younger than me, don't fully understand the circumstances and hardship of WWII as it is very distant, misunderstood and removed from our feelings and everyday life. We know what we see and read through literature and television programs but that is about the extent of our knowledge. By following my subjects throughout their everyday lives now and the hardships they face from war injuries both physical and mental, I came to further sympathize and further connect with their tragic stories – stories that were hidden and created great shame for these survivors. The archival materials were important for me to understand that time and place in Japan and I hope they add to the viewer's overall experience. So to answer your question, yes archival materials and photographs were made as the project progressed and as I interviewed and followed the survivors and how they live now in contemporary society burdened by an unspeakable past. Although when I started I didn’t have any of the family or personal connections with any of the WWII survivors I now feel I do.

"We cannot imagine the war time as a real situation. Even myself, I can understand how difficult and tough it would have been to survive after WWII with a disability, but I cannot sympathise from my heart."

KH: What I admire about this project is how all the different aspects of the publication work together to tell a very complex story. I believe the tweed cover also has some significance to connecting the overall narrative – can you talk more about this?

KO: Yes all the elements are connected, perhaps the cover is not as obviously as others. It was almost impossible for many survivors whose legs had been injured by aerial bombing to work again postwar. So they did sewing work and they could earn an income independently. This type of work also enabled them to hide from the public and work inside their apartments. This is a powerful representation of how survivor's stories have been hidden behind closed doors. This is why the cover is hand stitched tweed.

KH: There are so many complex elements to the book – how do you see them functioning together for the viewer who does not know much about what happened and a long time ago?

KO: One of the very difficult problems for my generation who didn’t experience WWII, or haven't heard of these tragedies directly from relatives who have, is lack of ability to sympathise with their stories. We cannot imagine the war time as a real situation. Even myself, I can understand how difficult and tough it would have been to survive after WWII with a disability, but I cannot sympathise from my heart.

From the interview text itself in the book, it might be very difficult to sympathise their situation for our young generation. However, the material I insert to book stimulate our heart. For example, Ms. Anno who lost her left leg when she was 6 years old, painted their legs to erase them. She also folded pictures to hide her legs. I inserted the replica of this picture in the book, so readers can see and fold this picture as she did 70 years ago. Another example is the propaganda magazine, which I chose to make a replica of also. I was really amazed when I found these magazines in a used book shop in Tokyo. Because these images are very strong and the government told lies very directly. In my experience in history class from elementary school to university, I had never read or seen this propaganda magazine. However this magazine was published in 370 issues and more than 300,000 were printed in April of 1942. I think all these elements could help the reader to understand this complex situation during the post war period.

KH: Photographer Rob Hornstra and writer Arnold van Bruggen’s The Sochi Project has been labeled “slow journalism”. The project is a combination of the Aperture published photobook, newsprint publications and an interactive website that documents Sochi leading up to the Olympic games. What do you think of this term and is it relevant to your own practice?

KO: I suppose Aperture dare to use the term ‘slow journalism’ to compare current media situation (instant information) such as Twitter or Facebook and so forth. Although these kind of slow (long term) journalism was existence from golden age of photojournalism (Walker Evans, W. Eugene Smith, Robert Frank, etc.), In our current situation, these long term projects with contemporary photography, attempt play a crucial role to represent this complex world. I strongly believe these kind of project fascinate our young generation who get used to using modern gadgets and supplementing the instant information. Under this meaning of slow journalism, I would like to try to be one of the slow journalists to attempt to represent complex situation.

KH: What next for Kazuma Obara?

KO: As of last month, I've moved my base from Osaka to London, and I am just starting my new project Atomic Theory (tentative title). The history and current situation of workers who have/had engaged in the nuclear industry, especially from plants that have had severe accidents in several countries. Although this is long term project, I think I can finish my first dummy this May.

Read part two of this interview here.

Hand made photobook "Silent Histories" by Kazuma Obara from Kazuma Obara on Vimeo.

In this interview with Dr. Kristian Haggblom and James Bugg, Fuji discusses the background of his project Hiroshima Graph - Rabbits abandon their children, how it fits into a larger ongoing project on similar themes, and how it relates and differs to his successful 2014 book Red String.