Interview: Kazuma Obara Part 2

Silent Histories - Part 2

An Interview with Kazuma Obara by Kristian Haggblom

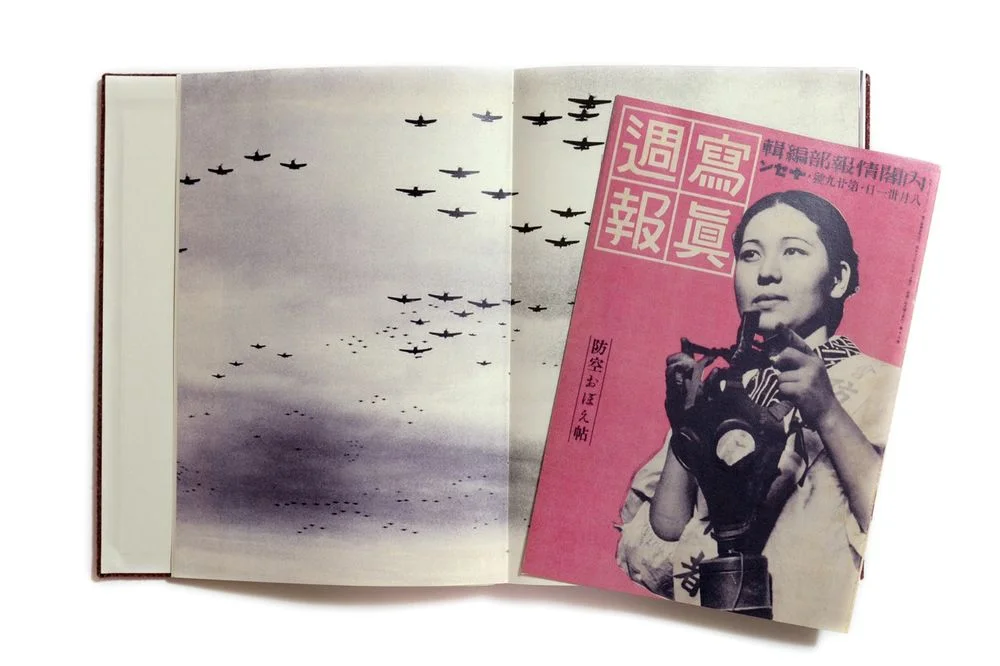

Kazuma Obara's Silent Histories is a delicate and complex look at the devastation of war. In this interview with Dr. Kristian Haggblom, Obara discusses the aftermath of the release of his award winning book. He also lets us in on his new Chernobyl project, and further explores Asian war atrocities through his new projects.

KH: Obara-san, since our last discussion Silent Histories has been greatly successful and published as a trade edition by RM Verlag in 2015. Can you tell me about some of the success the book has had and what this success has enabled you to do (workshops, photography festivals, etc)?

KO: The book has received great attention in many countries and it helped me to believe the power of photobooks. When my very first work about Fukushima was published in the newspaper, the reaction was also huge, but it did not continue for a long time. The story was consumed instantly. I know there is different types of roles in each photographic work and medium, but what I like from my experience is the book remains somewhere on someone’s bookshelf. In addition to this, I still receive feedback from people who bought it, even after four years have passed from initial release, and the book opened another door of the photo industry. I was engaged with my work mainly on newspaper and magazines before publishing Silent Histories. The books opened the other side of the industry which is more like conceptual documentary or the art industry that I didn’t know or understand prior. Before Silent Histories, there was no chance to show my work in photo festivals but now my work has been mainly exhibited in at international festivals.

I have also had and continue to get offers to run dummy photobook workshops. Since I started to make handmade dummies, it became my style to develop the ideas for each project. Now I am sharing the ideas and the process of making books – not only as objects but also conceptually with an emphasis on long-form projects.

This year, I will have workshops in Switzerland, Turkey and Russia. Understanding wider approaches to social issues, I can be more free from conventional photojournalistic styles. This is an enormous help and influence on my work and of course helps to gain further exposure.

KH: Please tell me about your work in Chernobyl, how it relates to Silent Histories and the self-published photobook titled 30?

KO: Since I engaged the project in Fukushima, I needed to think about what will happen for the people in Fukushima in the next 10 to 50 years. In 2015 while thinking about this I realised that it was the 30 year-anniversary of the Chernobyl nuclear accident. This influenced me to start planning to visit Chernobyl in the Ukraine. I started sharing my early ideas with various publishers in Europe. Before showing my work, they were really negative,because almost all publishers already produced books about Chernobyl. They told me, if your work will not be really really unique, it is quite difficult to publish on this theme. During the 30 years since the disaster Chernobyl had been consumed in many different ways and I began to recognise this.

As I did with Silent Histories, I started to collect found images from victims and archival images from the Soviet Union. Then I started to combine all materials with my interviews in one book dummy. The dummy was like Silent Histories, but I couldn’t find any strong concept and power to tell the story. From this dummy I started making different types of books with different approaches for 15 months. Until the closing stages of the project, I had made around 40 different version of the book. The result is the final photobook which consists of two books: and newspaper replica of newspaper and the handmade book in an edition as 30 each enclosed in a wooden box. The edition number is 86. In 2017, Editorial RM published 1900 copies as new edition. The ideas repeated from Silent Histories, a total run of this project became 1986 which is the year of Chernobyl nuclear accident.

These are brief descriptions for each project:

EXPOSURE is first project to portray a young Ukrainian woman who suffers ongoing thyroid disease as a result of Chernobyl nuclear disaster. She worries that her disability is invisible to the world. The images were created by using 30-year- old Ukrainian medium format films which were found in the Chernobyl exclusion-zone. Long exposure and experimental process created abstract images. The images give the space to the audiences and those images and long texts evoke the reader’s imagination to feel at least a tiny little part of her long lasting invisible pain.

EVERLASTING is second project captured the commute of the Chernobyl power plant workers between their hometown and the plant as a metaphor for the cycle of repetition. Decontamination work has been handed down from generation to generation since the accident. Given the difficulty of dealing with radioactive waste it seems as though this process could go on forever. Pictures of workers on the train and seasonal changes through the landscape from train’s window bring the narrative of this long lasting effects, life and work in Chernobyl.

KH: It is a very complex project how did you manage to hold it all together so it is coherent?

KO: Since I engaged the project in Fukushima, I decided to bring different perspectives to each subject explored. Focusing only on one side of the nuclear accident is not enough to think about this issue – it is far more complex. I believe it is better to get a neutral position to find the solution and also explore plural perspectives. In Japan, we have a continuing ideological and pointless discussion about disaster. Largely, because many people stand only on one side and are unwilling to dig deeper.

For my project, I try to bring three different perspectives. First is perspective from nuclear labour workers. The second from patients of the nuclear tragedy. The third is from government propaganda. So the project is published as three objects which are two books and one replica of Soviet era newspaper – this technical is representative of the three ‘voices.’ Each contain quite different contents, but I think each design of three objects help to combine those different perspectives.

KH: You are continuing your investigations from Silent Histories and 30 to explore Japanese war atrocities in the Asia region through Bikini Diaries and other projects. Can you elaborate in this new?

KO: Now I am focusing on histories and victims of WWII in South-East Asian countries. In 2015, one of the few public war museums in Japan that had exhibited material relating to Japan’s invasion of Asia, removed all such material on the orders of local government. Japan’s status as the only country to suffer a nuclear attack and lack of history education in Japan about Japanese occupation period has created a perception of national victimhood from WWII.

With a few exceptions, there has been little public recognition of the evils of Japanese aggression overseas. Even though many western countries such as Britain, Australia, The Netherlands and US have been telling POW stories for a long time, the brutalities of Japanese soldiers are not discussed or well known in Japan.

I am focusing on the victims who are invisible to Japan. At the same time, however, some stories, especially the Asian victims, are also invisible from western countries and relate specifically to colonialism before and after WWII. Again, I am trying to bring very different perspectives into one project and show the invisible victims and long lasting effects of war and suffering.

Thus far, I have been researching and shooting in Malaysia, Singapore, The Netherlands and the UK. I am also going to visit Korea, Burma and Thailand this year and – of course – hopefully Australia for this project.

KH: Do these projects function as ongoing ‘chapters’ that are interconnected and could all be read as a whole?

KO: Yes. All my works are connected, even if the theme itself is different.

KH: Do you feel there will be any backlash from Japan through these sensitive investigations?

KO: Yes. My work has caused some controversy in both Japan and Europe. The far right government of Japan have continuously tried to rewrite or delete parts of our wartime history. In some way, they have succeeded to do this. As a result, some minorities, including the invisible people I document, have become less important, misunderstood and further ignored. I would like to challenge and cope with this situation through my photographic work.

Read part one of this interview here.

Handmade photobook "Silent Histories" by Kazuma Obara from Kazuma Obara on Vimeo.

In this interview with Dr. Kristian Haggblom and James Bugg, Fuji discusses the background of his project Hiroshima Graph - Rabbits abandon their children, how it fits into a larger ongoing project on similar themes, and how it relates and differs to his successful 2014 book Red String.